As a child, a number of games appeared in our

family life, brought to us by my grandmother, the very ones played by my mother

when she was a child in the 1940s. These included such enduring classics as

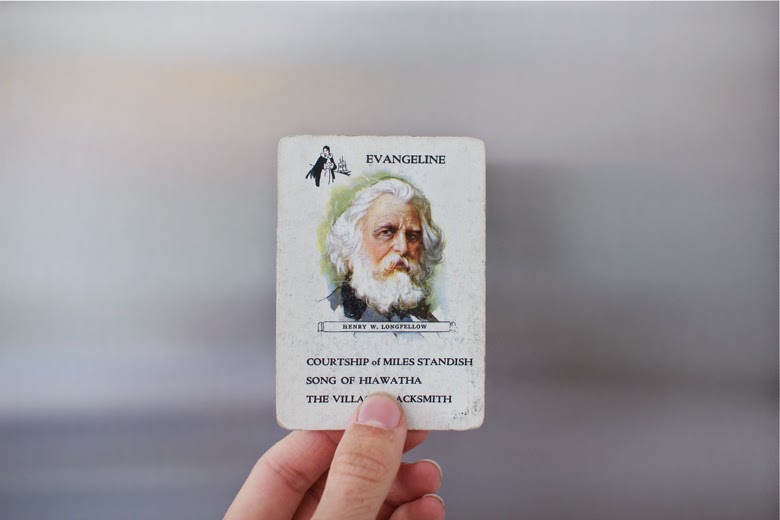

vintage Monopoly and Parcheesi boards. Also included was a card game called

Authors, popular in the U.S.A. (where my mother grew up), yet all but unknown

in Canada. It was meant to be educationally exemplary, an Old Maid-variant

devised in the 1860s wherein a great figure of literature (with a decidedly

American slant) were portrayed along with four of his (or her, the lone female

being Louisa May Alcott) most well known titles. The goal, of course, was to

extract cards by a particular author from your opponents and notch up a complete

set of four to your “library.” In addition to concentration on the game, there

were aesthetic pleasures to the cards in your hand, the soft-style period

illustration bust portraits, small-print identification on a banner across the

author’s chest and silhouette vignettes in the top left corner that

encapsulated each title with an image.

As a result of numerous days spent with Authors,

I formed lasting ideas about literature, which I did not bother to examine further by actually reading any of these books. A stereotypical boy, I

suppose, my preference was to gather titles of adventure writers like Robert

Louis Stevenson, James Fenimore Cooper and Mark Twain, with William Shakespeare

thrown in for good measure, an acknowledgment of the local proximity of the

Stratford Festival. What readings of the “classics” I did in my youth were almost strictly via Classics Illustrated

comic books, choices of which never intersected with the “literacy” that I

acquired by playing Authors.

Last month, at the St. Lawrence Antique Market,

I found a more recent deck of Authors, dating, I would guess, from the late

50s. Only a few of the authors represented were the same—Alcott, Stevenson,

Twain and Charles Dickens —their portraits, while derivative of those in the

earlier set, were, to my eye, cruder, and the titles selected to represent them

were different. Light blue replaced the black print. Instead of individual

silhouettes for each title, a generic line drawing was repeated four times for

every author. The new names included Howard Pyle, A.A. Milne, Hans Christian

Anderson and Rudyard Kipling. Louisa Alcott was no longer the lone woman, the

new set adding Cornelia Meigs (completely unknown to me). Someone had been

inspired to bring children’s literature to a child’s game. However, there is

something disconcerting about the probably all-too-accurate portraits of the

adult authors, typically stern or sallow countenances. Even to a grown-up me,

their faces trigger shuddering memories of fearsome Grade Four teachers and

school principals.

Guest contributor Ben Portis

No comments:

Post a Comment